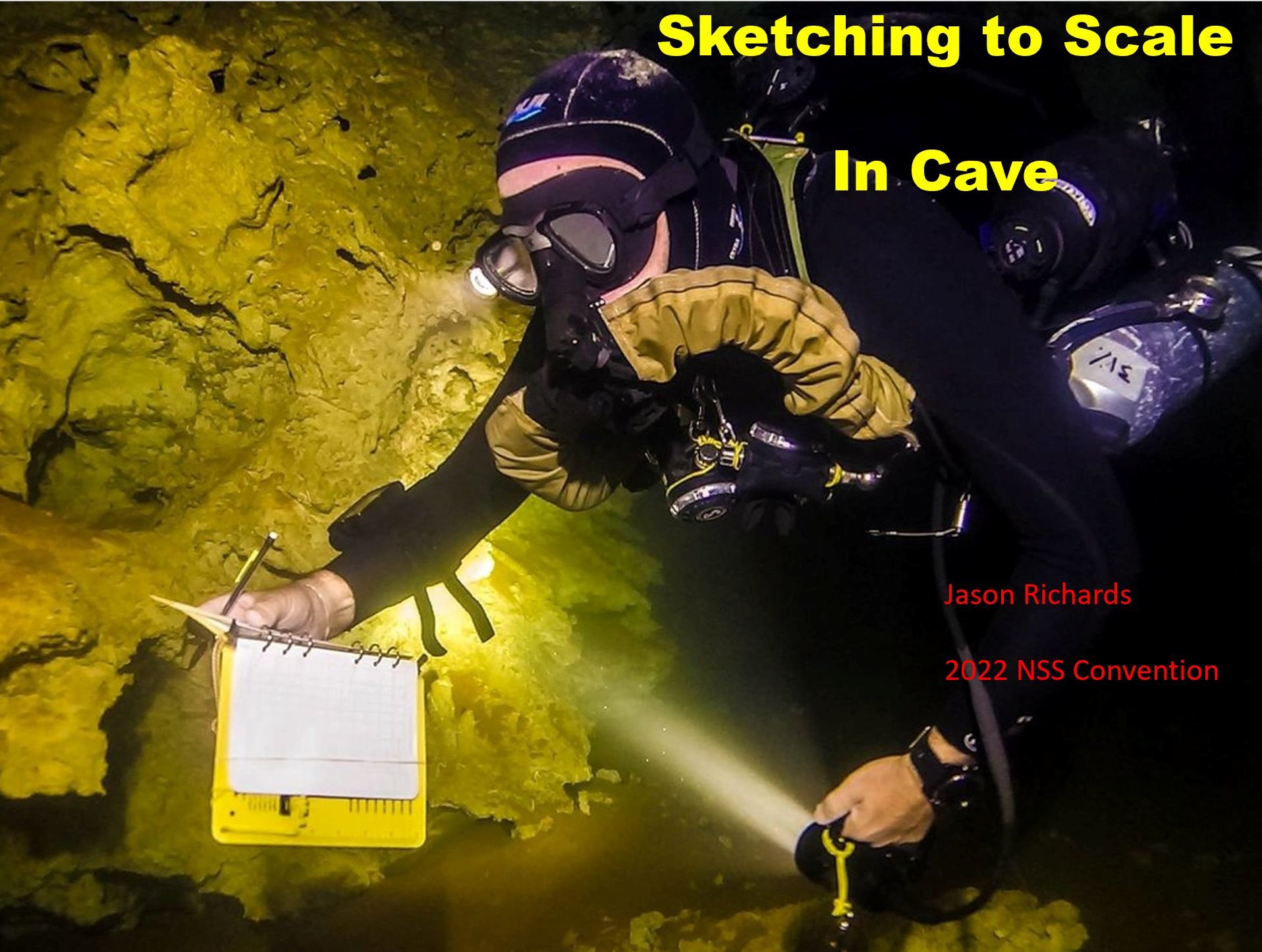

On Friday of Convention, I held the annual Survey Class, where, with the help of Chrissy Richards, Charles Walker, and Michael Roberts, we taught 25 students in class, and took 15 students out to Unnamed/Crystal Cave, with many thanks to the friendly cave owners and the Paha Sapa Grotto for making the introductions.

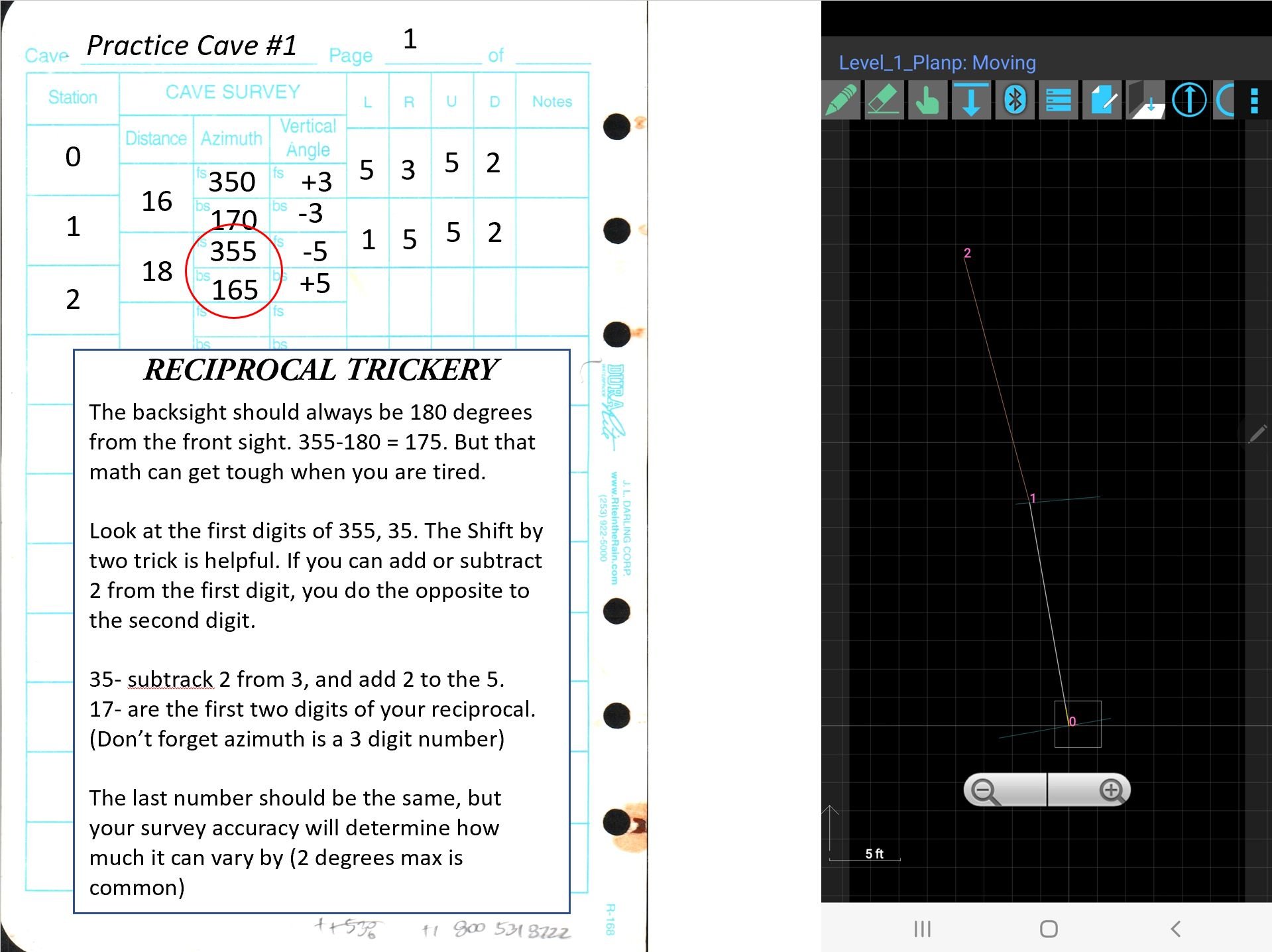

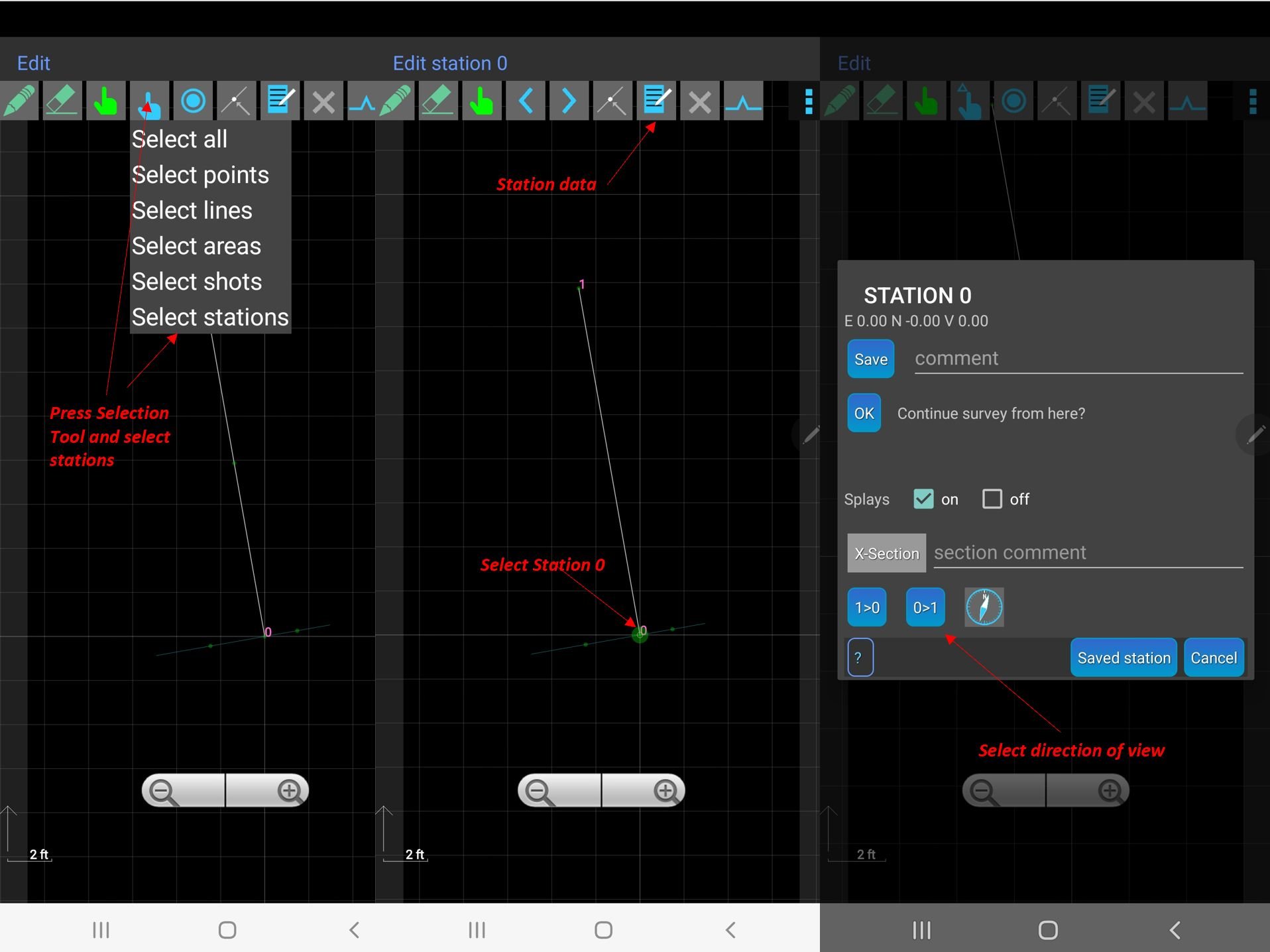

For the first time in the history of this class at Convention, we taught (or attempted to teach) both analog and digital cave survey using Topodroid. It went alright, and people learned some things, but wait for the 2023 class in Elkins, WV, or the 2024 class in Sewannee, TN. Class is going to be the bomb!!

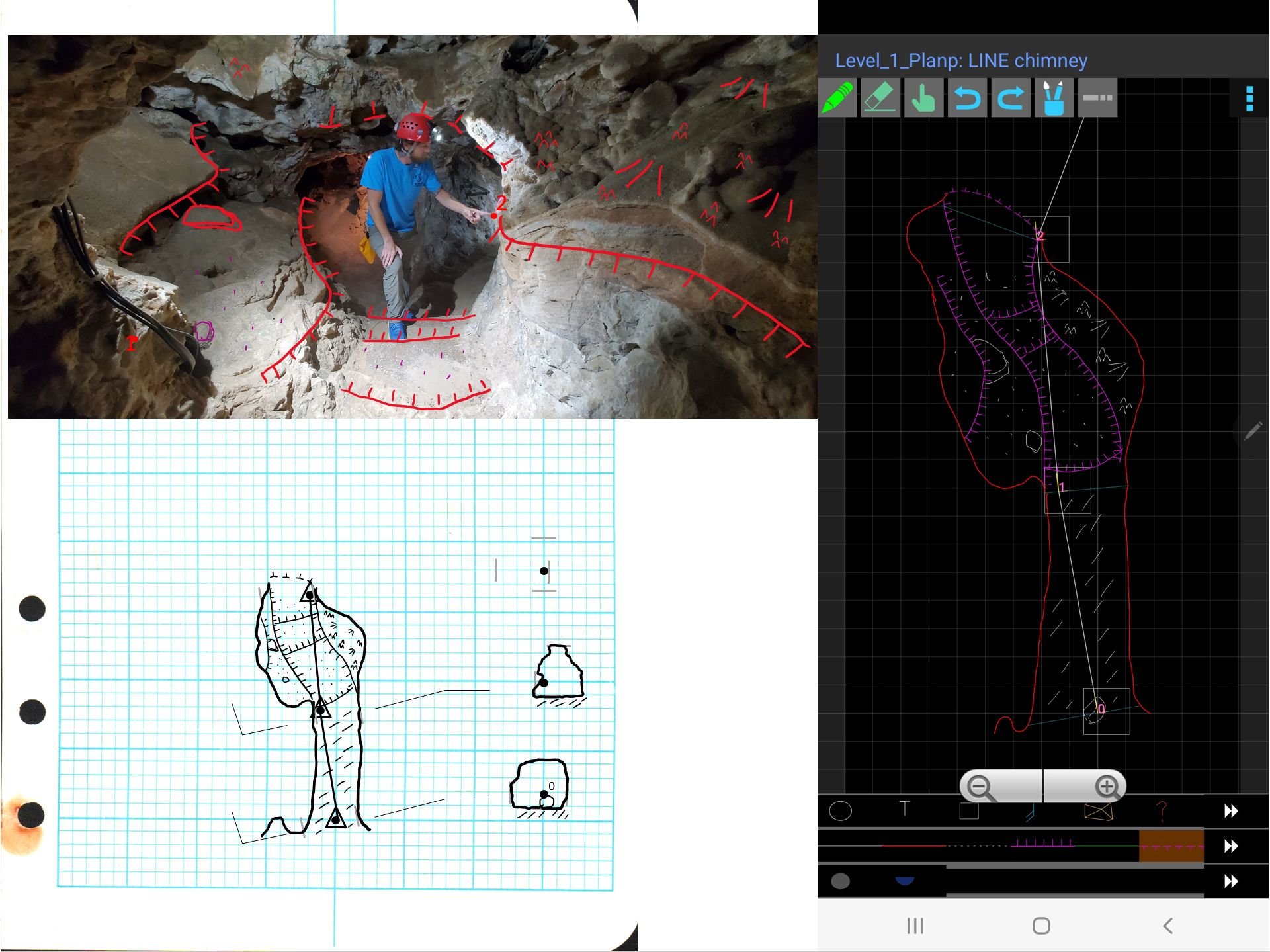

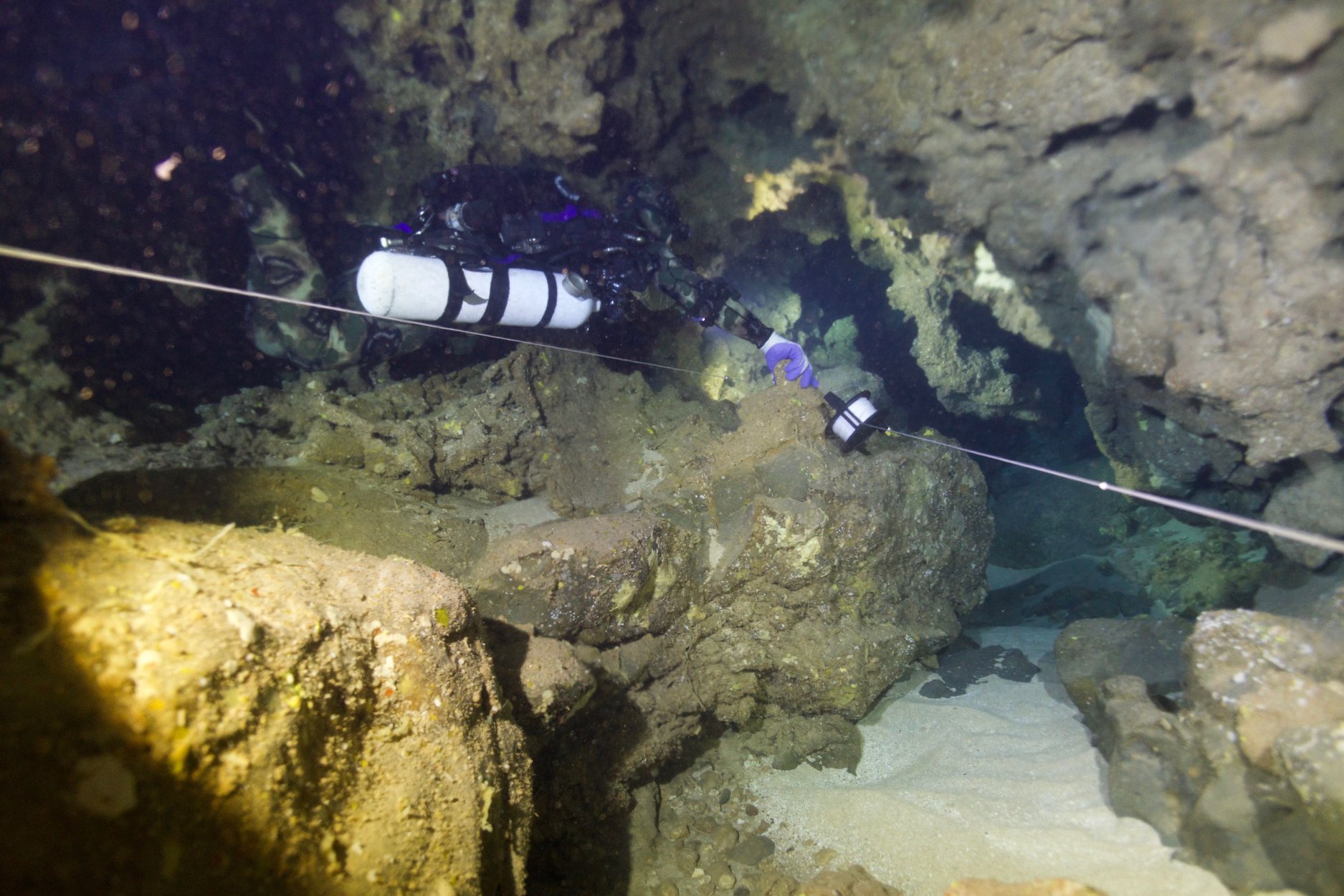

Following the classroom portion we headed out to the cave! Here part of the class started sketching (with help from instructors) on either paper, or on their android sketching tablet with Topodroid!

You can view the slides from the classroom portion (with notes) from this link: See the Slides!